Seasons of Joy and Sorrow

Michael McKee was Louis Fulgoni’s life partner and, ultimately, his primary caregiver. Here, he recalls the multitudes Louis contained.

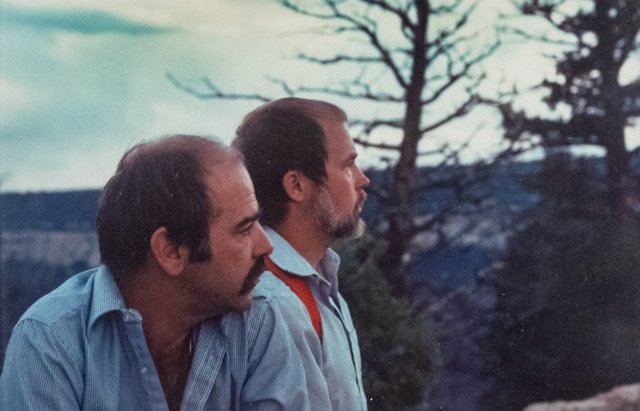

Louis Fulgoni (left) and Michael McKee at the Grand Canyon in July 1982. Photo by Emily Margolis.

Life with Louis Fulgoni was not easy. We lived together for more than fifteen years, and most of the time we were inseparable. When we first got together in February 1974, we had apartments four blocks from each other in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. We toggled from what we called Southwold, my place on 17th Street, to Northwold, his abode on 21st Street (this was a reference to the British TV series Upstairs Downstairs, which we watched every week). After three years, the burden of paying two rents led to a decision to give up my apartment. I still live in the 21st Street apartment, since 1992 with my husband Eric Stenshoel.

A couple of months after we first met, I think it was April, I arrived home in the afternoon to find Louis frantically packing. I asked what was going on. Louis informed me that he was going to Montreal for the weekend. He was super agitated, so it was clear that something had happened to spook him. After a few minutes of conversation, he agreed that I should accompany him. An hour or so later we were at Penn Station waiting to board the overnight train. He had calmed down and was jovial, and we had an enjoyable four days away. I have no idea what had set off this episode and I knew not to ask.

By now, I was aware that Louis was prone to panic attacks and there was no way to predict when one would occur. For the first few years of our relationship Louis never left home without a Valium in his jeans pocket. Years later, long after he had given up regular use of Valium, we were driving to Staten Island, where Louis had grown up, when a sudden attack happened on the Gowanus Expressway. Fortunately, I was at the wheel. When we arrived at his mother Mary’s house on Wilson Terrace, Louis sat outside on the terrace in front of the house while I went next door. I knew that Mary’s cousin Anita O’Neill would have Valium, and as soon as Louis took it the panic abated.

In all the time we were together, I never knew what to expect when I arrived home from the office. Sometimes Louis would be in an exuberant mood, giddy even, eager to talk. He spent most days in solitary confinement with his work, whereas my work involved non-stop talk whether in meetings or on the phone, so I was sometimes tired and not feeling chatty. Other times I walked in to find Louis in a dark state, wrestling with demons. I used to describe this as a black cloud hanging over his head. In the parlance of the time, he demonstrated elements of a manic-depressive personality.

But the joys of living with Louis outweighed the difficulties. We shared the same interests and saw the world through the same lens. Louis was never boring. In social settings he was the life of the party. His death in July 1989 threw me into an emotional tailspin and a state of agitated depression that lasted for well over a year.

Louis as a young child on a visit to Central Park, late 1930s.

There is no way to understand who Louis was without discussing his relationship with his parents, Adolph and Mary. He was an only child, and his parents were absurdly overprotective. For example, they would not allow him to take swimming classes for fear that he would drown. Consequently, Louis had a lifelong dread of going into a swimming pool or the ocean. I once tried to teach him how to float in the shallow end of a pool, but he could not relax enough.

Unlike Louis, I grew up with two younger brothers, and I came to understand how difficult it can be for an only child. Louis told me that he had invented an imaginary younger brother named Joey and pretended to play with him. Joey was also the name of his first teenage boyfriend. One time, Adolph caught them in bed together. He told Louis that if he did that again he would have him circumcised; he also took his son to a chiropractor, presumably to “cure” him, something Louis laughed about later.

Adolph and Mary never got over the fact that when he was twenty-five years old, Louis finally moved out of their house and took up residence with his boyfriend Frank in Queens. Louis told me that it took him several years to get up the courage. This was taboo at the time. In Italian American society in 1961, sons lived with their parents until they married – preferably an Italian Catholic girl – and started a family. The departure of their unmarried son could mean only one shameful thing, and Adolph’s oldest brother Henry Fulgoni who lived in Queens (dead long before I came on the scene) angrily demanded that Adolph force Louis to return home.

Adolph never accepted the reality that his son was gay, and Louis never came out to him. Only after Adolph died in 1979 did he have a conversation with his mother, which made life easier for both of them.

I knew Adolph for the last five years of his life and thought he was a horrible person. He was a bully and a womanizer who had become a full-time invalid by the time I met him. Adolph had a series of health problems including diabetes, asthma and emphysema owing to years of heavy cigarette smoking, as well as congestive heart failure, which ultimately killed him. Mary was his full-time nurse. He ordered her around, and whenever he was unhappy with her actions, he criticized her rudely and loudly in front of everyone. This drove Louis crazy and made me uncomfortable.

Louis disliked his father intensely, which meant that we made only three trips to his parents’ house on Staten Island every year, for dinners on Easter Sunday, Thanksgiving and Christmas. Adolph was a superb cook; for several years he was executive chef for General Electric at their Manhattan headquarters and had retired with a decent GE pension. I remember the first time I had pommes Anna, which he made for Christmas dinner that first year.

The Fulgonis had a cottage in Phoenicia in the Catskills, where they spent summers until they sold it in 1978. That year, Adolph suffered a bad asthma attack. Because Mary did not know how to drive a car, there was a long delay waiting for an ambulance to take them to the nearest hospital in Kingston, at least half an hour away. Being so far from emergency medical care was now too dangerous.

In July 1974, we had gone to Phoenicia for a weekend with my brother David and his then-wife, who had relocated to New York City for a couple of years. I had already met Adolph and Mary when we went to Staten Island for Easter, but this was the first time I had spent more than a few hours with them. The four of us stayed in a motel near the house.

For Saturday lunch, Adolph made a veal roast. I was sitting next to him and remarked how wonderful it was with all the garlic he had used. He then proceeded to tell me a long story about Louis’s Aunt Peggy, who was divorced from Mary’s older brother Silvie. I struggled to follow this interminable tale, the gist of which was that Peggy was from Piemonte and a terrible snob – I discovered this was basically true once I met her – and that the Piemontese, they “dinna-wanna pay the tax to Italy, they wanna pay the tax to Francia, and that’s why Aunt Peggy she don’t like garlic.” (Adolph was fluent in English but spoke with a pronounced Italian accent.) Both Mary’s and Adolph’s families came from Bardi, a little town in the northern Apennine Mountains southwest of Parma.

That night we were watching TV news, which was mostly about the Watergate scandal. Adolph was scornful: “Yeah, they gonna do to Nixon what they did to Mussolini.” Louis and I had many a laugh afterwards about the prospect of seeing Richard Nixon strung up by his heels at a gas station in Milan.

Another time we were on Staten Island watching the news after a holiday dinner, and the announcer mentioned women’s liberation. Adolph erupted: “Every! Time! I hear! That Women’s! Liberation! I get sick! To my stomach!” This triggered an immediate, severe asthma attack. Louis spent the next hour or more walking his father back and forth in the dining room until he was calm enough to sit down.

“Manhattan Tantra,” print on paper with colored ink, mid-1980s. This collage of vintage New York City skyscrapers (with the Staten Island Ferry terminal at bottom) evokes Louis’s journey from the insular Island to wider horizons in the city.

In the weeks leading up to Christmas 1979, Adolph’s health worsened. He was admitted to the ICU at Doctor’s Hospital (now demolished) near the house on Staten Island. A couple of days before Christmas we took the ferry and bus out. The ICU allowed only two visitors at a time; Mary’s cousin Eddie Costello was with Adolph, so Louis went in while I waited in the hallway, where a choir was serenading everyone with Christmas carols. Considering the setting and the condition of the patients, there was something sinister in the cheerful demeanor of the carolers.

After fifteen minutes or so, Eddie left. When I entered, Louis was staring daggers at his father, who brightened when he saw me. “Michael! You’ll fix my car! My son, he don’t want to fix my car,” he said. For the next several minutes I listened in utter confusion as Adolph tried to explain something about a part that needed to be replaced and kept repeating that I would take care of it. (A few days later, Eddie, Louis and I looked under the hood and figured out what Adolph had meant.)

As we walked to the bus stop for the return to Manhattan, Louis said over and over: “I hate him. I don’t care if he is my father. I hate him.” I said nothing. I don’t know what Louis had expected by way of a deathbed conversation. Finally coming out to his father? Not likely. Some kind of end-of-life reconciliation? A lesson about car mechanics?

During our life together, Louis would go through periods when he would see his therapist, then he would stop, then later go back. He had been in therapy for a while before we met. I never met this man and don’t remember his name, but what I do remember is his description of Adolph and Mary Fulgoni: “the Staten Island deaf mutes” who could not hear or speak of discomforting truths.

Adolph died the following evening, after we had been summoned back to Staten Island. I never saw anyone look more relieved the next morning than Mary. During Christmas dinner the two of us were outside on the terrace briefly, getting some bright winter sun. Mary said to me, “I’m so happy that my son has such a wonderful friend.” For her, this was a bold statement.

We now began spending more time with Mary. We went to Staten Island many weekends, and one of us would go out to take her to the doctor or on other errands. Her brother Silvie had forbidden her to learn to drive because it wasn’t lady-like. We took her to California for three weeks in August 1980, accompanied by our friend Oebel Harmsma. Following her husband’s death, Mary seemed happier and much more relaxed.

“Sex Death,” etching on paper, mid-1980s. Although Louis created this image before his HIV/AIDS diagnosis, it reflects his deep concern about exposure to the virus that was spreading rapidly in New York.

In late July 1987, Louis and I were spending a few days in eastern Long Island. On Friday morning he told me that he felt dizzy, a bit light-headed. The specter of AIDS had been hanging over us for years, and though neither of us uttered the word, we both thought it. I called to make an appointment with our doctor that afternoon and we set off, but unexpectedly heavy west-bound traffic on the Long Island Expressway caused us to arrive in Manhattan after office hours. On Sunday Louis told me he did not want me to go with him Monday morning.

But the next morning he changed his mind and asked me to accompany him. By the time we arrived, everyone – doctor, nurses, receptionist – had concluded that Louis was HIV-positive before they did any testing. It all had a fatalistic air. Diagnosis was PCP, an ancient form of pneumonia that people with weakened immune systems could contract, and one of the two most common illnesses suffered by people with AIDS. (When the ELISA test for HIV had become available in 1985, I suggested that we take it but Louis, always superstitious, said emphatically no. After he was diagnosed, our doctor got me tested and by some miracle I was negative.)

We spent two weeks in the cooperative care unit at NYU Medical Center while Louis was treated for PCP. The first evening we were there Mary came to visit; instead of returning to Staten Island, she would spend the night at our apartment. Our friend Tony Torres, who lived across the street from us, was also visiting. He had contracted PCP a few months before. The conversation was awkward because we were trying to learn from Tony’s experience without tipping Mary off.

Before she arrived, Louis and I had agreed that I would tell her that he had AIDS when I took her back to the apartment, before returning to coop care for the night. In the cab I rehearsed what I was going to say. But when we arrived home, the phone rang. It was Louis, who had changed his mind: “I don’t want you to tell her.” The moment I hung up, Mary asked me, “Is there anything you want to tell me about this illness?” I didn’t think that my answer – “No” – could have been convincing. Like her son, Mary had paranoid feelers and a keen sense of when she was being gaslighted. But she did not pursue the subject further.

For a couple of days, I argued with Louis, telling him that Mary needed to know about his situation. Finally, he said, “You don’t understand. If my mother knows I have AIDS, I won’t be able to see my mother.” I immediately got it: Mary’s reaction would be so protective, so smothering, and would drive Louis so crazy, that he would stay away from her.

Back then the disease seemed to take a predictable course for most people with AIDS. After the initial infection, things felt normal for a year or year and a half, at which point an opportunistic infection, or more than one infection, would take over and gradually weaken and then kill the patient. This was the pattern with Louis as well as with others we knew. AZT, the first drug approved for AIDS treatment, was supposedly going to keep them going, and Louis took it faithfully. Only later was it determined that AZT was not only ineffective but also damaging.

From late July 1987 through the end of 1988, Louis was able to function, and he did not he look sick. Louis wanted to see Gothic cathedrals in France, so we made a three-week trip to Paris that October, which included excursions to Normandy and Provence. Our friends Susan Butler and Ian Walker crossed the channel from the U.K. and spent a week or so with us. It was on this trip that Ian took a memorable photo of Louis with a dog outside the Chartres Cathedral.

Louis and friend outside the cathedral at Chartres, France, in October 1988. Photo by Ian Walker.

Sometime in early January 1989, Louis developed chronic diarrhea. Then he was diagnosed with cryptosporidiosis, which is caused by a ubiquitous, tiny parasite that people with intact immune systems fight off handily. For months I tried to imagine where he had contracted it. Could it have been the assiette anglaise, the plate of cold cuts he had for lunch in that tiny town in the Alpes-Maritimes as we drove through the mountains en route to Nice? Finally, I realized the source had to be New York City tap water. Once he was diagnosed with AIDS, I had tried to persuade Louis to drink only distilled water, but he pooh-poohed my concerns and continued to drink straight from the tap.

By February, Louis was having trouble eating and had lost a noticeable amount of weight. Mary had left to visit relatives in Florida, so for his fifty-third birthday on February 7 he went to the house on Staten Island and holed up. He left no note, and I didn’t know where he was. When I called the house, he answered but was unwilling to talk about anything.

A few weeks later, we were back for another stint in NYU coop care. Then, a couple of days after he was sent home, I had to call 911 and we took an ambulance to St. Clare’s Hospital where Louis spent an additional couple of weeks. He came home once more, but after less than a week we were back at NYU. Even though Louis was too sick to qualify for coop care, we managed to get him admitted until a bed opened up in the adjoining Tisch Hospital a few days later. He never left the hospital again. For three and a half months I slept on a cot in his room on the AIDS floor, going home once a week to get the mail and water the plants. As soon as I arrived, the phone would ring, and Louis would ask when I was coming back.

Louis continued to lose weight. This is why they refer to AIDS as the wasting disease, I thought. We agreed to have a port installed near his collarbone so he could receive liquid nourishment, and his weight stabilized, although he didn’t gain any. Eventually this open wound became infected, leading to a blood infection, high fever, a coma, and the septic shock that killed him.

Throughout the two years of his illness, I adopted the unrealistic view that if I could just find a magic bullet, Louis would not die. Once we were ensconced on the AIDS floor at NYU Tisch Hospital, I heard about a drug, Diclazuril, a veterinary medication that had been used successfully in Europe to treat AIDS patients with cryptosporidiosis but had not been approved for humans in the U.S. – even though it was commonly used to treat farm animals infected with the parasite.

Our friend Sandra Abramson had a doctor friend in Brussels who happened to work for the company that manufactured Diclazuril. I spoke with the infectious disease doctor at NYU who agreed to administer the drug if we could obtain it. Sandy’s friend made a trip to New York, and Tim Ledwith, Louis’s business partner, met her at the airport and brought the illicit meds back to the hospital.

That night I ran into the mother of a patient down the hall. I had often seen her outside her son’s room in tears. She asked, “Is it your friend who is taking the Diclazuril?” I realized that everyone on the seventeenth floor must know. Many patients were there because of crypto. We were all looking for that magic bullet.

The drug was toxic, so the protocol was seven days on, then seven days off. The doctor started Louis on the lowest dose, which did nothing, then after a week off he doubled the dose. Again nothing. Another seven days off and this time he doubled the dose again. After four or five days at this amount, the diarrhea stopped. The next day Louis ate solid food for the first time in months. I thought we had turned a corner, but in the middle of the night Louis developed a high fever and was delirious. By midday he was in the ICU on a ventilator. Eleven days later he was dead.

Portrait of Mary Fulgoni, print on paper, c. 1981. Louis made this portrait of his mother when she was in her early seventies. Mary would survive her only child by two decades.

By early March 1989, it had become clear that Mary was aware of the truth. AIDS was on TV news every evening. Still, the deaf-mute pattern continued; neither mother nor son acknowledged the reality. I had a constant feeling of guilt about not telling her, but I felt bound to honor my partner’s wishes.

We were between hospitalizations on Easter Sunday, March 26. Mary traveled into Manhattan to have dinner with us and our next-door neighbor Carl Frisk at a Chelsea restaurant, but Louis was too weak to venture out and stayed in bed. He had lost more weight since the last time she saw him. After the meal we returned to the apartment. Mary stood next to the bed for several minutes and held her hand against her son’s cheek, not saying anything. Louis was clearly uncomfortable but also said nothing. Carl walked her to the bus stop.

Once we were in a room at Tisch, Mary and her cousin Anita made weekly trips to Manhattan, by bus, ferry and bus, then back to Staten Island the same way. Each time, Anita brought flowers from her garden. I remember the sequence of blooms from April to July: narcissus, lilac, iris, lilies. Neither of them ever asked any questions about the medical situation, which was a relief, but I couldn't shake the feeling that I was being more hurtful than if I had leveled with Mary.

Early on the morning after Louis developed the high fever, I called Mary and told her to pack a suitcase and plan to stay indefinitely in Manhattan. Kathy Mahoney, Anita’s daughter who lived with her mother next door to Mary, drove her in to the hospital. One of the nurses let us use a small conference room. I took a deep breath and announced, “He has another infection.” Mary and I both started crying. Kathy put her hand on Mary’s.

The next eleven days are a blur. As ICU visiting hours were restricted, we settled into a ritual, making a daily trip to the hospital in time for the first visiting period, sitting in a lounge between visits, then returning to the apartment for a late dinner after a long day. Louis awoke from the coma twice. The look on his face the first time he regained consciousness – plain horror at finding himself with a tube down his throat and hooked up to machines – was like a knife through my heart. I held his hand and said through hot tears, “Louis, please don’t hate me for putting you on the ventilator.” He squeezed my hand.

I discussed the medical issues with Mary each day, but without mentioning AIDS. One night Mary came out with, “I guess my son just doesn’t have anything to say to me.” I didn’t know how to respond. The next morning, she told me over breakfast, “I had myself a good cry last night.”

Self-portrait, oil on canvas, 1988. Louis’s final self-portrait was also one of the last paintings he was able to complete.

Louis died around 5 p.m. on July 26. I walked into his ICU room to find about eight doctors and nurses, all women, surrounding his bed. The monitor showed that his blood pressure was astonishingly low; if memory serves, it was around 42 over 20-something. One of the doctors was blowing air into his lungs with a small device that looked like a bellows, and Louis, though unconscious, was heaving. I felt faint, weak in the knees, and dissolved into tears. A couple of the nurses grabbed me and rushed me out of the room. This all took only a few seconds. Why did I allow them to remove me?

That evening, back at the apartment, I told Mary, “I’m sorry I wasn’t more honest with you, but there were some things Louis would not allow me to tell you.” For the rest of her life, I let her think that Louis was protecting her, when in truth he was protecting himself.

Mary asked me if Louis had specified what he wanted by way of services. I had been dreading showing her his will, in which he instructed cremation, forbad any viewing of the body, and forbad any service. Mary read the will and handed it back to me: “I want you to do exactly what he wanted,” she said.

But a couple of weeks later, after a group of us had accompanied the hearse to a New Jersey crematorium, there was a mass for Louis at St. Sylvester’s, Mary’s parish on Staten Island. No remains were present. His ashes, later scattered in Lower Saranac Lake, were in a closet on 21st Street. I never asked, but I assumed that Mary had ordered the mass. I decided to attend. I cried through the entire service.

A parent never gets over the death of a child, and when it’s an only child it has to be worse. Mary lived another twenty years and, except for the last couple of years, was in robust health despite high blood pressure and a bout of cancer when she was ninety. She lived alone, cooked breakfast and lunch for herself, did her own laundry and kept a tidy house. We went out virtually every weekend to shop for groceries, and my husband Eric made a week’s worth of meals which he froze in containers, so all Mary had to do was pop them in the microwave. One or both of us accompanied her on doctor visits. We took Mary to Italy twice, in 1994 and again in 1997 (the second time with her cousin Dorothy Mazzella) to visit family in Genoa and Bardi.

A month before her ninety-sixth birthday Mary tore a rotator cuff in her right shoulder. Surgery at her age was out of the question, so she had to live with it. As she was right-handed and very right dominant, everyday tasks became difficult. Soon we had arranged for home health care, and after only a few weeks we had to provide it 24/7. For a while Mary was frail but mentally intact, but gradually she descended into dementia. Her personality changed, possibly because of the dementia or possibly because she had a couple of mini-strokes, which her doctor suspected, but they could not be detected. A lifetime of suppressed anger began to manifest itself, and she dropped all attempts at her usual lady-like behavior. One evening I reminded her that it was time to take her pills. “I’m not taking that shit,” she declared. In more than thirty years, I had never heard her utter such a rude word.

There were occasional psychotic episodes. One Saturday she started yelling, “Help! Somebody help me! Help!” This went on for a good hour. I called Mary's doctor who advised taking her to the emergency room, but Eric and I were reluctant to take her there, especially on a Saturday when it was guaranteed to be crowded. Eventually, Feyi Savage, the weekend home health care aide, was able to calm Mary down.

Another time, Mary turned to me and said, “Who are you?” I replied, “I’m Michael.” Mary said, “Yes, I know. But how do I know you?” I went through a lengthy explanation, but she did not recognize the name of her son, nor the names of her father and mother. Suddenly she cried out, “I don’t understand what’s happening!” She put her hands over her face and started bawling. Feyi told me to go to the grocery store and said Mary would calm down. Sure enough, when I returned she was back to herself. Feyi explained that Mary had napped for a while and when she woke up the confusion had been forgotten.

Mary died in January 2009, a couple of months after her ninety-ninth birthday. Eric and I were happy that we were able to keep her in her home, even though for the last several months she didn’t know where she was. Her dream life had become more real than actual life. About a month before she died, Nancy Mulbah, the best of the home health care aides, called me one evening, saying that Mary wanted to talk with me. She passed the phone to Mary, who asked, “Michael, I’m down at the ferry. Are you coming to get me?” I replied, “Just wait for me, Mary, I’ll be there in a few minutes.”

“First Black,“ oil and gesso on canvas, 1988. Louis's penultimate painting suggested a new stylistic direction in a body of work that had spanned four decades.

Louis lacked the ability to promote his work. He rarely expressed interest in doing so, which I believe was part real and part defense mechanism. He did participate in an occasional group show, and occasionally entered an art contest. He had no problem hustling for commercial art jobs, and he was quite good at that. But when it came to his painting, prints and drawings, it was as if he had a block. Somehow, he once persuaded art dealer Ivan Karp to come to the apartment to look at his collages. Karp was impressed, saying that these were some of the best works he had seen in a long time. I tried to persuade Louis to follow up, but he never picked up the phone or wrote a letter.

Twice, Louis talked to me about the 1970 fire that destroyed some 400 of his paintings. He described standing in the window of his apartment above The Angry Squire pub on Seventh Avenue and watching as his studio across the street went up in flames. This was four years before we met, but I remember the fire well: it was in a two-story loft building at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 23rd Street, now replaced by a pedestrian apartment building. Before the fire, Louis said, he painted rapidly and instinctively. Afterwards, he worked more slowly and deliberately. When I knew him, he produced between three and six paintings a year. He sold a few but remained ambivalent about marketing his art for the rest of his life.

Once Louis was diagnosed with AIDS, I became obsessed with finding a cure, in denial about the likelihood that he was going to die. This blind obstinacy had the result of making his death more difficult for me to process. I went into a months-long funk, stayed up every night into the wee hours reading or watching television. I drank a bottle of wine a night, and some nights ate an entire pint of ice cream straight out of the carton. I felt alienated from my work on policy and advocacy for tenants’ rights. This has been my life’s work for more than fifty years, but for a period after Louis died, I felt like I was going through the motions. My primary care doctor put me on Prozac but after a month I decided I couldn’t stand it and stopped. In early 1990, he referred me to a grief counselor who, over the course of several months, helped me emerge from depression.

During this time, I focused on cataloguing Louis’s art. Through a colleague from Rochester, I met a young photographer, Matthias Boettrich, who during a few weeks in 1990 photographed some 200 of the works, delivering slides of the highest quality. Most images in this exhibit, “Louis Fulgoni: Memory + Legacy,” were taken by him. More recently, another photographer, Rick Bajornas, digitized the slides and shot many additional pieces that Matthias did not get to. (Some Fulgoni works are missing; I have no idea where they might be. Tim Ledwith and I hope that the retrospective we have organized will result in locating some of them.)

In the years since Louis’s death, Tim and I have had many conversations about the need to organize a retrospective. The failure to get this done has weighed on me. It is now my wish that this virtual retrospective will be the beginning of an overdue recognition of the art of Louis Fulgoni.